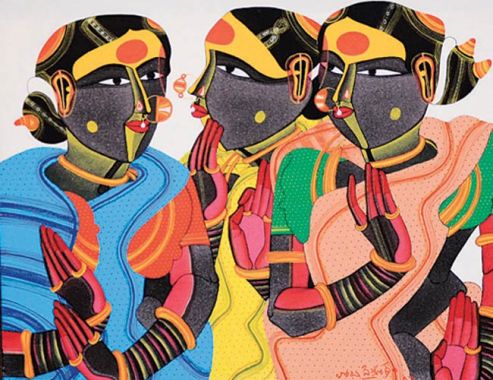

Knowledge about any spatial location can be understood in multiple ways. The body, as space, can be perceived as an ultimate frontier of complexities. To merely view the body as a biological entity is to restrict its form of communication. Instead, the body should be viewed as a site of culture imbued with powerful aesthetic, which is symbolic of socio-political meaning. If one were to further elaborate on the idea of the ‘body as a cultural site’, one could perhaps say that the body is an artefact upon which humans reinforce cultural norms and hierarchies, as well as de-attach themselves from the way the body itself has been marked, fetishized, and molded in compliance with existing human ideologies.

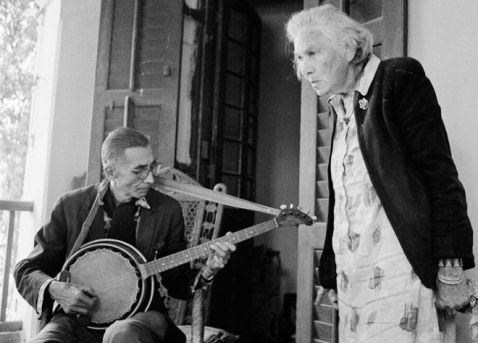

When we talk about the body it also becomes important to talk about aesthetic experience, that is, how the body is a reflection of the complex interrelationship between the self and society. Furthermore, the aesthetic experience is a powerful dynamism in the development and maintenance of one’s individual as well as group identity. For example, a manipulation of the bodily aesthetic is a remodeled presentation of self, therefore the desire to change the fundamental order of one’s sense of personal identity, and how this sense of selfhood is to be viewed from the eyes of the other.

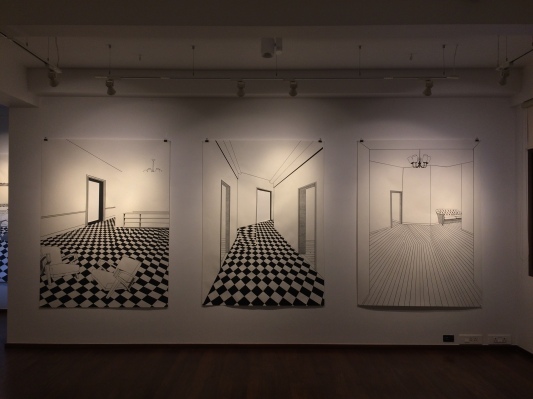

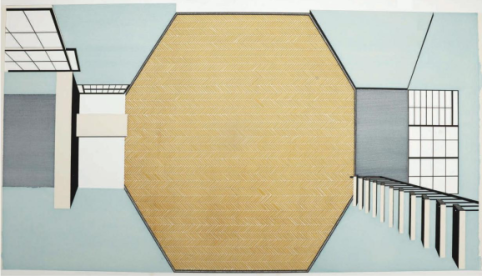

Let me also point out that when one hears the term ‘aesthetic experience’, one often tends to think of an experience associated with a museum or art gallery. However, the aesthetic experience is very much part of one’s personal life and is not simply restricted to formal spatial locations. An aesthetic experience in relation to the body marks a ritualization in which one’s sense of being/self is etched by aesthetic decisions. Any noticeable changes in the aesthetic self-presentation are often associated with the individual’s changing perception of themselves, and of their place in society.

From a contemporary feminist point of view, the aesthetic experience of the body is a topic that feminist artists are constantly engaging with. Women artists have embraced performativity in their art practice because of its ability to not be confined by the unchanging permanency of sculpture and painting. Themes such as sexuality, beauty, domesticity, are being critiqued by women artists who are re-claiming a feminist space for critical reflection.

Indian feminist artists such as Pushpmala N and Sonia Khurana, amongst others, are aiming to create a world within which women get to re-write notions of beauty and ‘feminine’ expression. Their expanding idiom of art practice is situated within the context of the feminist critique of the correlation of women to the prevailing dominant power structures and systems of representation. Their performances go beyond a language of acceptance which render females as passive, with the body always assuming an active role.

Moreover, feminist art practices not only act as mediating sites between one’s selfhood and bodily aesthetic but also as mediums through which women can reclaim their bodies and express who they are, here and now. Through their visual vocabulary, they break away from traditional notions of eternal femininity, and gravitate towards a contemporary notion of ‘femininity’. Through engaging with the body as an active, political tool, feminist artists highlight female subjectivity and identity.

So how does feminist art contribute to the aesthetic experience? Its contribution lies in its ability to provoke, disturb, and critically question the existing socio-political milieu. It is through this disturbed aesthetic that feminist art strives to affect and bring a change towards a gender-equal space. To insert the body within feminist art practice offers a new dialogue between the body and society. In other words, it aims to understand the body’s continued effort to articulate and challenge issues of domination and vulnerability within the patriarchal system.

Engaging with the body through feminist art gives way to liberation, opens up ways to reverse power dynamics, as well as aim to launch a further inquiry into the everyday aesthetic experience. It is through the site of the body that one protests, questions, and critiques existing paradigms. So what is the aesthetic experience? Simply put, to understand one’s body beyond the realm of its physicality and to use the body as a medium for understanding one’s place in the world.